MUMBAI: Unprecedented in our lifetime, the havoc that the outbreak of Covid-19 brought about has left, among other sectors, the sports industry in absolute disarray.

As sports, and cricket – from an India perspective – looks to limp back to normalcy in the coming months, there’s much to worry about as the game’s economy lies in a shamble. Few understand the sport’s global and local economics from a bird’s eye view like Sundar Raman.

The former chief executive officer of the Indian Premier League (IPL) – who worked on the T20 property since inception and was one of the senior working hands at the International Cricket Council (ICC) – is keeping a close watch on how things have been spiralling out. Raman has been working on a white paper that looks into cricket’s present crisis, the strain of the coming months and the possible cures the industry could look at in the short and long term. He shared those views exclusively with TOI.

If there was a debate between T20 World Cup or IPL, he reasons out why it should be IPL as no sport can afford financial turmoil currently. In Raman’s view, it’s a case of an annual property alone generating close to 40% of cricket’s global revenue versus a global property that has the comfort of being rescheduled to a later stage.

IPL alone, he says, guarantees US$100m in players’ salaries annually (Rs 85 cr per franchise multiplied by 8). That accounts for broadcast revenues of at least three to four member-boards of the ICC put together, underlining what’s at stake for players financially on a global scale where India’s T20 league alone is concerned.

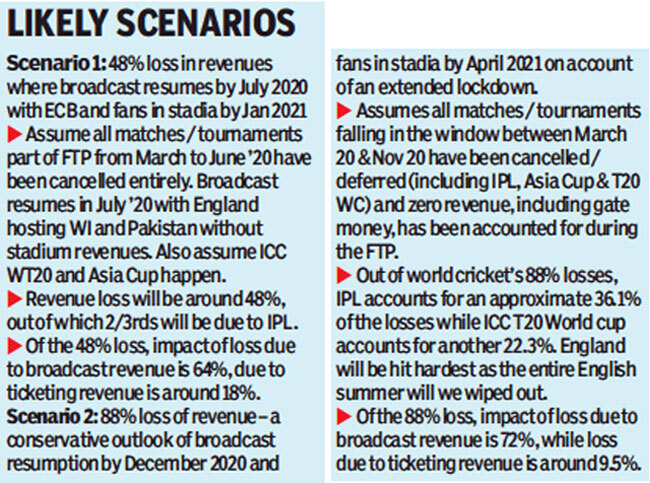

Raman has worked on two likely scenarios that may play out in the coming months:

Scenario 1: Sport returning to TV/Digital platforms by July 2020 and fans in stadia by January 2021

Scenario 2: Sport returning to TV/Digital platforms by December 2020 and fans in stadia by April 2021

Focus of this paper, says Raman, is to bring to light the delicate economy of sports with a focus on the global cricket landscape across three most important revenue streams of the sports economy viz media / broadcast revenue, sponsorship revenue, and match day (ticketing) revenue and the impact of Covid on the overall ecosystem.

With the global cricket economy estimated to be around US$1.9b and a strong reliance on India (nearly 2/3rd of the revenue are generated on the back of playing in India or India participating), India realises only 45% of its overall potential, thereby enabling other nations to monetise.

“This potential opportunity of India’s revenue contribution (unrealised by India) is alone worth US$ 1.2b over a 4-year cycle (2019-2022),” he says.

A third of cricket revenues in 2019 were from the IPL. With a fair market pricing structure, approximately 24% (US$ 100m) of the broadcast rights fee earned by IPL is spent as player wages each year.

In 2019, despite being a Cricket World Cup year, IPL revenues were estimated to be 30% higher than that of the World Cup (not including ticketing revenues of CWC as those are retained by the host). IPL 2020 revenue was projected to be 70% higher compared to ICC WT20 revenues in 2020. With current uncertainty around both these events, this remains a hypothetical scenario. Raman says “Cancellation of both these events will have a serious impact on cricket economics for this year.

However, in the case of an ICC event, as the contracts run through till 2023, a deferment to 2022 may be possible without loss of revenues. Not hosting IPL or bi-lateral season of any country will lead to a loss of revenue, which is far from desirable. In an ideal world, the ICC event scheduled in 2021 in India could be shifted to Australia as it is in the same October window and India could host the event in 2022 by creating a suitable window. This will give adequate time for economic recovery and not overcrowd the calendar”.

Also, if WT20 is to happen behind closed doors, host Australia’s gate revenues will be zero. For the IPL even if it is held behind closed doors, the impact is smaller as it is cushioned over 8 stake holder teams and the economics of IPL can still support a closed-door season.

“IPL remains as the single biggest event for the global cricket economy. With a contribution of around 1/3rd of global cricket revenues annually, the importance of IPL cricket’s global economy cannot be over stressed. If IPL was to be considered a separate cricket body and revenues from IPL were to be removed from the Indian cricket boards revenues, IPL would emerge as the biggest revenue generator for global cricket – higher even than ICC & ACC revenues combined,” he says.

Therefore, given the large contribution and annual nature of IPL, cancelling the event would be a severe loss of revenue to the cricket economy, something that no sport can afford in the current economic environment. Whilst the jury is still out on ICC WT20 this year, deferment (of World T20) merits serious consideration.

The paper further states: Whilst India realises US$ 863m, the attributable value of revenues from Indian participation is estimated at US$ 1.2b. This delta of US$ 300m+ per year can be viewed as India’s opportunity loss or in a more positive outlook as India’s contribution to cricket outside India. Over a 4-year period this value is a staggering US$ 1.2b. Lucrative broadcast and sponsorship deals of ICC & ACC events are also primarily driven by the huge Indian fan base and high viewership from India. Media reports put TV viewership for the ICC CWC 2019 Final between England and New Zealand played in England at 15.4 million on Sky in England and at 183 million in India.

Also, out of the total 706 million unique broadcast audience for ICC ODI world cup 2019, 509 million were from India. This dependency on India is also evident from the relatively low value realised by global broadcasters through sublicensing from all other markets despite the events being hosted in some of those markets.

“The importance of India to the world cricket economy cannot be over stressed. Outside of Australia and England, who have large domestic market deals, both valued at US$ 1b over a 4-year cycle, other cricket boards rely on Indian tours as part of bilateral fixtures to attract interest from Indian broadcasters,” says Raman.

For countries where domestic market deals are not large, tours from countries such as India, England or Pakistan become important as they open up substantial overseas broadcast rights, which are substantially larger than domestic rights.

Many cricket boards have provisions in their broadcast deals on the number of games to be played against India during the deal period. Not fulfilling this can adversely impact the broadcast rights value realisation. Given that most of these boards are sitting without broadcast rights and play within a US$ 35 to US$ 45m revenue bracket, they haven’t been considered in the paper that looks at a global meltdown, hence the primary players.

Source : timesofindia