Scientists have found a new way to probe into supermassive black holes – detecting their properties like mass and spin by observing how they rip apart stars. They have found a model which can infer black hole mass, its spin by observing how the stars are ripped apart on coming to the vicinity of these astronomical bodies with high gravitational force found at the centre of some massive galaxies.

Scientists have found a new way to probe into supermassive black holes – detecting their properties like mass and spin by observing how they rip apart stars. They have found a model which can infer black hole mass, its spin by observing how the stars are ripped apart on coming to the vicinity of these astronomical bodies with high gravitational force found at the centre of some massive galaxies.

Most black holes lead isolated lives and are impossible to study. Astronomers study them by watching for their effects on nearby stars and gas. Stars are disrupted when the black hole’s tidal gravity exceeds the star’s self-gravity, and this phenomenon is called tidal disruption events (TDE). This model, which can be applied after the star is observed to be tidally disrupted, and an accretion disk is formed, will help in expanding our understanding of the physics besides building valuable statistics of the black hole mass and stellar mass.

Supermassive black holes govern the movement of stars orbiting within their gravitational potential, and their tidal forces can disrupt or rip apart the stars that come to their vicinity. Scientists from the Indian Institute of Astrophysics (IIA) who had earlier calculated the rate of disruption and its statistics, focused on the observations of a given stellar disruption event (TDE) in their new study and inferred the black hole mass, star mass, and the point of closest approach of the star’s orbit. T. Mageshwaran (now at TIFR), as a part of his Ph.D. thesis work at IIA with his supervisor, A. Mangalam (IIA), developed a detailed semi-analytic model of the dynamics of accretion and outflow in TDEs. Their research was published in the New Astronomy (2020).

The stars in a galaxy are captured and ripped apart about a few times in a million years. The disrupted debris follows a Keplerian orbit and returns with a mass fallback rate that decreases with time. The infalling debris interacts with the outflowing debris resulting in the circularization and the formation of an accretion disk – the temporary accumulation of matter outside the back hole before it dives into the black hole. This emits in various spectral bands from X-ray, optical to infrared wavelengths. The transient nature of TDE luminosity makes it an ideal laboratory to study the physics of an evolving accretion disk that includes the gas dynamics of the inflow, outflow, and the radiation.

The team predicted the detection of stellar disruption by black holes and related emission via viscous accretion from the formed disk by simulating the evolution of luminosity for TDE disks in various spectral bands. They used the prediction to infer the mass and spin of the black hole.

The tidal disruption events are crucial and useful phenomena to detect and predict the mass of supermassive black holes in quiescent galaxies. This time-dependent model by IIA provides insights into disk evolution in a black hole gravity.

The scientists further explain that the infalling debris forms a seed accretion disk that evolves due to mass loss by accretion onto the black hole and wind but gains mass by fall-back of the debris.

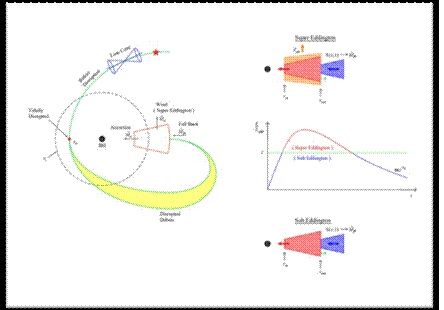

Figure 1: Left: The star with an orbit, in the loss cone in phase space, which takes it inside the tidal sphere. A schematic structure of accretion disk showing the accretion rate, mass fallback rate, and mass outflow rate.

Right: The top figure represents the disk structure at different phases. The blue, red, and orange shaded regions show the mass fallback of debris, the disk structure, and the wind structure, respectively. The black arrows represent the inner and outer radii of the disk. The wind is launched from the photospheric height (zph). The right arrow at outer radius implies an evolving outer radius. In the middle plot, the light curve evolves through different phases.

The highlight of this model is the inclusion of all the essentials elements –accretion, fall back, and the wind, self-consistently, in a formulation that is numerically fast to execute and shows good fits to the observations compared to the earlier steady structure accretion models.

This time-dependent model simulates the luminosity, which along with the capture rate of stars for tidal disruption, black hole demographics (population distribution of black holes in the Universe), and instrument specification of survey mission, results in the expected detection rate of TDEs. By comparing the expected detection rate with the detection rate from observation, one can probe into black hole demographics. The fits to the observations yield parameters of the star and the black hole that are useful for the statistical studies and build the demographics of black holes.

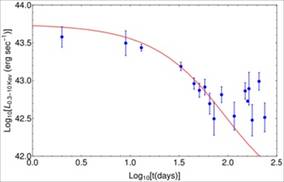

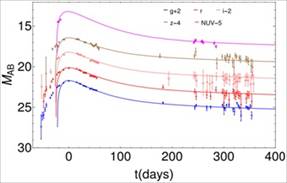

Figure 2: The super-Eddington model fit to the observations. Left: The X-ray observation of XMMSL1 J061927.1-655311 (Saxton et al. 2014) with the obtained black hole mass is 8 million solar mass, and star mass is 8.3 solar mass. Right: The PS1-10jh observation (Gezari et al. 2012) with obtained black hole mass is 6.8 million solar mass, and star mass is 1.1 solar mass.

[References:

1. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1384107618303099?via%3Dihub

Mageshwaran, T. & Mangalam, A., 2021, New Astronomy, 83

2. https://iopscience.iop.org/article/10.1088/0004-637X/814/2/141

For more details, Prof. Arun Mangalam (mangalam@iiap.res.in) can be contacted.]