Solar flares or sudden explosion of energy caused by tangling, crossing, or reorganizing of magnetic field lines near sunspots and active regions, has been probed by scientists for years, and much of it still remain a mystery.

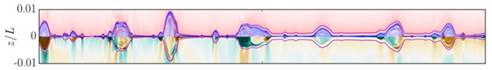

In order to delve deep into the intrigue of the solar flares, solar physicists have explored the first evidence of a significant number of plasma blobs, which they have observed associated with the biggest solar flare of the decade on September 10, 2017. Their statistical analysis of the plasma blobs or plasmoids, which are aftermaths of the solar flare, reveals a very hot current sheet with temperature over 20 million Kelvin.

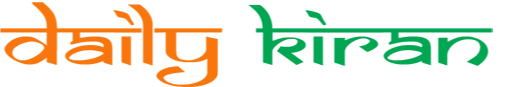

Figure 1: Standard flare-CME model depicting a current sheet between the post-flare loops and the ejecting flux rope that forms a CME. (Yuan-Kuen Ko et al. 2010)

These current sheets are formed when magnetic fields of opposite polarities come close to each other and reconfigure, giving rise to a phenomenon called magnetic reconnection. This process is accompanied by the release of large amount of energy stored in the magnetic fields very fast and drives the eruption (CME) as well as heat the local plasma. Thus, the current sheets are often very hot.

Recently, the solar physicists at Aryabhatta Research Institute of Observational Sciences (ARIES) Nainital, an autonomous institute under the Department of Science & Technology (DST), Government of India, along with their collaborators from the Instituto de Astrofísica de Canarias (IAC), Tenerife, Spain and the University of Oslo, Norway, used the imaging observations from NASA’s Solar Dynamics Observatory (SDO), and Solar and Heliospheric Observatory (SoHO), and KCor coronagraph in Mauna Loa Solar Observatory (US), to observe a very hot current sheet with temperature over 20 million Kelvin associated with the biggest solar flare of the decade observed on September 10, 2017. This study will appear in an upcoming issue of the Astronomy and Astrophysics journal.

The research provides the first evidence of significant number of plasma blobs along with the current sheet in the wake of a solar flare that could help delve deeper into solar flares.

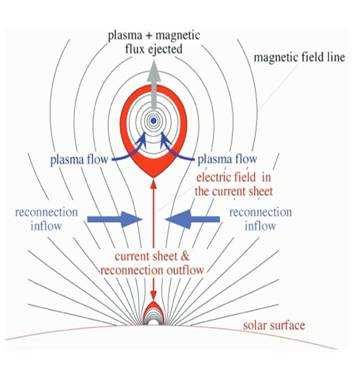

Figure 2: An example of plasmoids observed in simulation by Huang et al. (2017) in the top panel. The observed plasmoids in SDO/AIA observed in 131 Å wavelength images presented in this study. It could be seen that multiple plasmoids are observed at an instant, as predicted by simulations.

It could be a step further in our understanding on the role of formation of plasma blobs in current sheets for dissipating a large amount of magnetic energy in a short time during or after solar flares.