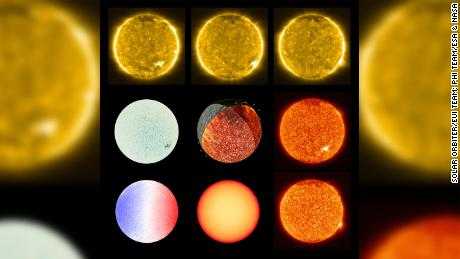

NASA released the pictures on Thursday.

Solar Orbiter is an international collaboration between the European Space Agency, or ESA, and NASA, to study our closest star, the Sun. Launched on Feb. 9, 2020 (EST), the spacecraft completed its first close pass of the Sun in mid-June.

“These unprecedented pictures of the Sun are the closest we have ever obtained,” said Holly Gilbert, NASA project scientist for the mission at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland. “These amazing images will help scientists piece together the Sun’s atmospheric layers, which is important for understanding how it drives space weather near the Earth and throughout the solar system.”

“We didn’t expect such great results so early,” said Daniel Müller, ESA’s Solar Orbiter project scientist. “These images show that Solar Orbiter is off to an excellent start.”

Solar Orbiter carries six imaging instruments, each of which studies a different aspect of the Sun.

Normally, the first images from a spacecraft confirm the instruments are working; scientists don’t expect new discoveries from them. But the Extreme Ultraviolet Imager, or EUI, on Solar Orbiter returned data hinting at solar features never observed in such detail.

Principal investigator David Berghmans, an astrophysicist at the Royal Observatory of Belgium in Brussels, points out what he calls “campfires” dotting the Sun in EUI’s images.

“The campfires we are talking about here are the little nephews of solar flares, at least a million, perhaps a billion times smaller,” Berghmans said. “When looking at the new high resolution EUI images, they are literally everywhere we look.”

It’s not yet clear what these campfires are or how they correspond to solar brightenings observed by other spacecraft. But it’s possible they are mini-explosions known as nanoflares – tiny but ubiquitous sparks theorized to help heat the Sun’s outer atmosphere, or corona, to its temperature 300 times hotter than the solar surface.

“So we’re eagerly awaiting our next data set,” said Frédéric Auchère, principal investigator for SPICE operations at the Institute for Space Astrophysics in Orsay, France. “The hope is to detect nanoflares for sure and to quantify their role in coronal heating.”

Other images from the spacecraft showcase additional promise for later in the mission, when Solar Orbiter is closer to the Sun.